I'd like to describe a few of my own thoughts on how type II diabetes develops. By taking a step back and looking at a "big picture" overview of how this disease starts, perhaps this might help us make sense of it in a way that looking at too small a scale cannot.

Maybe this disease is not the result of something going wrong, but is the result of all the cellular machinery working exactly as intended, and then failing in an unexpected way when all of the parts fit together as a system.

The tragedy of the commons is "where individual users, acting independently according to their own best interests, behave contrary to the common good of all users by depleting or spoiling the shared resource through their collective action."

What is type 2 diabetes?

Type 2 Diabetes is a chronic condition is best characterised by high blood sugar level (above 7 mmol/L) and insulin resistance that then goes on to cause cardiovascular disease, retinal disease, etc through the formation of advanced glycation end-products. (read more here)

Usually, when we have a high blood sugar level (e.g. after eating a sweet!), our pancreas releases insulin. Insulin acts on our tissues to signal them to take up glucose into the cells away from the blood, thus bringing the blood glucose level back to normal.

In type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance means that the insulin that is normally released has less of an effect than in a normal, healthy individual. This means cells take up less glucose out of the blood, and so the blood sugar level stays elevated, and given enough time, this can result in all of the damage to our bodies mentioned above.

With the defining feature of insulin resistance, many people focus on the "insulin" part as the bit that is going wrong and causing disease, and we often use insulin to treat type 2 diabetes.

From the NHS website:

It's caused by problems with a chemical in the body (hormone) called insulin. It's often linked to being overweight or inactive, or having a family history of type 2 diabetes.

While technically correct, this kind of definition makes it sound like the insulin is doing something wrong, and if we could fix that then the disease would go away. And it makes it sound like if you have a family history of it, you are at risk whatever you do and it is not really under your control.

I think it's slightly more subtle than that.

Insulin is a signal for cells to take up glucose and store it

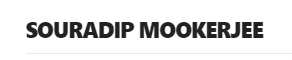

What does insulin do to get cells to take up glucose out of the blood? Here's a molecular signalling diagram explaining how:

Broadly, the sugar has to go somewhere. If it's not being immediately used (the most likely scenario, we tend not to exercise and eat at the same time!) then it is stored as glycogen.

What happens when the cellular energy stores get full?

What if this stored energy is never used? This is often the case in modern day society.

There has been no evolutionary reason to select for tolerance to this, as we have often lived in times of starvation in the past, not abundance.

Physically, a cell must only be able to store so much energy, beyond which it will no longer function. Perhaps there is a cellular stored energy sensor that eventually goes "hold up, there is no more room, stop taking up energy when insulin tells us to".

In type II diabetes, we see cells downregulate their insulin receptors and this means they become resistant and refuse to take up glucose. ** But what if this isn't a result of the disease causing them to downregulate these receptors, but simply a normal mechanism because they can't take up any more energy? **

What happens when too many cells refuse to take up glucose because they are too "full"?

One or two cells doing this would not be an issue, as we have plenty of cells that are able to take up glucose.

But what if after many many years we reach a critical mass of cells such that our blood glucose level slowly starts to slide out of control?

This would be the classic picture of type II diabetes as seen in endocrine clinics in hospitals.

This explains many of the features of how type II diabetes develops

We often think of type II diabetes as one associated with obesity, somewhat intrinsically linked as part of a "metabolic syndrome". I speculate that this large scale systems-based thinking of these components might help us make more sense of this cloud of symptoms and associated conditions.

Genes that predispose to the common forms of type II diabetes as discovered by GWAS studies have been largely to do with the brain. Specifically, appetite control. It is well known that given a high energy food environment, different individuals will respond differently, and a lot of it is thought to be down to how our brains are wired.

This is why it is an acquired condition rather than congenital, and largely affects people after a certain age once all of that excess energy has accumulated.

Also raises some interesting hypotheses - could people who undergo liposuction surgery be more at risk because they've lost their reserve of fat cells?

This model also explains how type II diabetes often develops very gradually (hence the term pre-diabetes). Our bodies have a lot of redundancy built in - as individual cells become "full" and stop responding to insulin, there are plenty of other cells that can pick up the slack. It is only when a critical mass of these cells are unable to take any more up that we tip beyond the threshold of a safe blood glucose range.

Many treatments affect some part of this pathway and explains their unintended consequences

This gives us a framework to think through the possible consequences of interfering with individual parts of this pathway, and whether it would truly be beneficial or not.

For example, some drugs (like metformin) act by fooling the cellular energy stores to take up more (thereby "decreasing insulin resistance"), while others (e.g. recombinant insulin) cause a higher activation in the insulin receptors left on the surface of these cells, stimulating them to take up more.

These drugs also have the side-effect of causing further weight gain - perhaps this is a direct consequence of its mechanism of action rather than a "side effect" as we often describe it, followed by resistance to treatment once patients reach their new "limit" of cellular energy stores.

We can use this model to generate new hypotheses

What implications does this have for how we treat this common condition? Do many of our front line therapies, by acting to fool these metabolic sensors actually make the problem worse by unleashing the consequences of overburdened adipose tissue and subsequent inflammation as they inevitably burst open?

If someone congenitally is born with less adipose tissue, is this the reason some very thin people develop type II diabetes, because they reached that critical mass of cells full of energy at a healthy BMI?

Does this explain why some very obese people live for years without suffering from obesity, because they had so many more adipocytes able to absorb all that energy?

I propose this might help us make sense of the often confusing data we get, and to put all of these findings into a framework, to turn all the associations between variables into a coherent story with causal relationships between each of the parts.

From the same NHS website,

It's a lifelong condition that can affect your everyday life. You may need to change your diet, take medicines and have regular check-ups.

Is it necessary for type 2 diabetes to be a lifelong condition? Or is it possible to change that perception by showing that it is simply the result of the body's energy stores being full, and that by emptying these stores it is possible to no longer have this condition? Various published case studies suggest so!

Conclusions

This is just a thought experiment based on my experience as a medical student on wards, lecture notes and literature review. I am open to new ideas, this has just been my interesting take on the "big picture" story of diabetes.